Written by Zsolt G. Pataki with Katerina Mavrona,

‘Hybrid threats’, i.e. actions aimed at harming their targets through overt or covert military or non-military means, are increasingly used by state or non-state actors seeking to undermine democratic societies, in pursuit of strategic aims, without the necessity of financing the real costs of a classical military aggression. Hybrid tactics threaten citizens’ trust in democratic institutions, exacerbate political polarisation, sow confusion through stealth and through concealment of attackers’ identities, and do so using tools that are widely available and therefore cost-effective (e.g. information distortion and its amplification through digital communication technologies). In this way, perpetrators, foreign governments or domestic affiliates, profit from turning civil liberties, such as the freedom of expression, into vulnerabilities to manipulate and attack. However, just as online platforms and social media help launch disinformation campaigns at scale, so can communication and digital technologies act as barriers to online subversion.

Ways to achieve this are the subject of the ‘Strategic communications as a key factor in countering hybrid threats’ study by Iclaves and commissioned by the European Parliament’s Panel for the Future of Science and Technology (STOA), following a request from the Subcommittee on Security and Defence (SEDE). Targeting audiences via online platforms is one of many instruments available in the hybrid threat toolbox. The study presents complementary tactics, including the funding of political parties and cultural organisations, employment of strategic leaks and cyber weapons, use of religious influence or the fuelling of concerns about migration. At the centre of these, however, the study discerns an all-pervasive ingredient: the informational component. Information manipulation can ultimately transform, exacerbate and distort people’s beliefs, attitudes or emotions. Yet, for the same reason, the authors highlight that information can redeem the impact of hybrid tactics and help counter disruptive narratives.

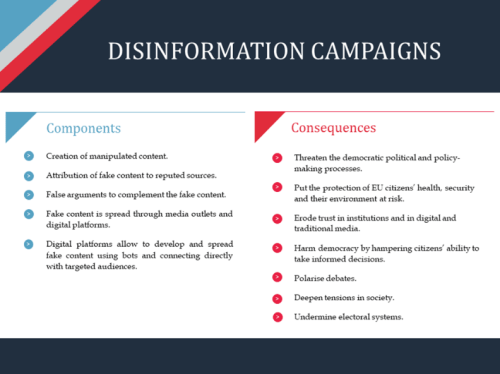

Disinformation campaigns begin with the manipulation of content, usually addressing real facts from a distorted perspective, rather than presenting audiences with entirely fabricated stories. While this strategy lends some credibility to promulgated narratives, it also requires that the message bypasses traditional ‘gatekeepers’: journalists, editorial desks or fact-checkers. Online platforms offer fertile terrain for successful manipulation: they act as technological enablers – perpetrators deploying bot accounts by the thousands to amplify narratives is routine practice today – as long as questions on platform responsibility for content moderation remain unsettled.

How can the cycle be broken? The taxonomy of responses comprises sequential stages of prevention, detection and response. Across these, the study examines different response actions, ranging from intelligence, legal, diplomatic or even military action to informational measures and initiatives. As the name implies, ‘strategic communications’ come into play with a twist, as they are not about disjointed responses to unsolicited adversarial activity, but are executed according to predetermined and systematic plans and are designed to advance distinct policy goals. As such, they demand high levels of coordination among stakeholders. What is more, strategic communications planners anticipate that audiences may find themselves in conflictual environments and subject to a constant ‘information buzz’ made up of distorted or blatantly false messages.

What do strategic communications entail for the EU and its Member States? While democracies face an asymmetric fight against actors with no reservations about deploying illegitimate methods or illegal tools, the response resides in adherence to the very principles under attack. Truthfulness and credibility, the understanding of cultures, ideas and identities, reliance on and practice of mutual comprehension are the themes upon which strategic communications are structured. To present and assess these ideas, the study explores seven case studies extensively, where hybrid tactics with informational components were deployed and concomitant strategic-communications-based responses were used (e.g., external financing of religious extremism in the Netherlands, foreign influence by Russia and China through academia and think tanks, the Russian intervention in Ukraine, disinformation campaigns against North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) operations in Lithuania). The study derives a number of challenges to effective strategic communications campaigns from these case studies, followed by targeted policy options.

What do strategic communications entail for the EU and its Member States? While democracies face an asymmetric fight against actors with no reservations about deploying illegitimate methods or illegal tools, the response resides in adherence to the very principles under attack. Truthfulness and credibility, the understanding of cultures, ideas and identities, reliance on and practice of mutual comprehension are the themes upon which strategic communications are structured. To present and assess these ideas, the study explores seven case studies extensively, where hybrid tactics with informational components were deployed and concomitant strategic-communications-based responses were used (e.g., external financing of religious extremism in the Netherlands, foreign influence by Russia and China through academia and think tanks, the Russian intervention in Ukraine, disinformation campaigns against North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) operations in Lithuania). The study derives a number of challenges to effective strategic communications campaigns from these case studies, followed by targeted policy options.

Likely digital solutions to disinformation include the deployment of artificial intelligence for detection, the use of hyperconnectivity – afforded by the upcoming 5G rollout – for conducting mass fact-checking campaigns, or investment in blockchain security to improve traceability and ensure the integrity and veracity of stored and disseminated information. In the study conclusions, the reader can find a comprehensive table listing the risks emerging technologies pose in the context of hybrid aggression, as well as the advantages they offer for defenders and policy-makers. To successfully incorporate technological options to strategic communication responses, however, a comprehensive policy approach is required, and this is reflected in the study’s policy options.

The proposed policy options extend from the regulatory domain to investment policy: the authors mention further EU legal framework harmonisation to specifically target hybrid threats, disinformation and foreign interference, arguing for example in favour of adaptations to the EU sanctions regime, and for streamlining upcoming regulation on artificial intelligence. They also make explicit reference to strengthening the Code of Practice on Disinformation, signatories to which are major online platforms. In the case of investment policy, greater use of financial instruments for innovation to close the technological gap between the EU and its global competitors is proposed. Finally, emphasis is also placed on EU initiatives for improving coordination across the hybrid-threat stakeholder ecosystem, both internally (in the EU) and with external actors and organisations, including NATO.

The STOA Options Brief linked to the study contains an overview of various policy options. Read the full report to find out more, and let us know what you think via stoa@europarl.europa.eu.